Mere Christianity Video Study

Here’s a C.S. Lewis resource it would have been nice to have back when we were going through Mere Christianity in Season 1 of the podcast:

"We are travellers…not yet in our native land" – St. Augustine

Here’s a C.S. Lewis resource it would have been nice to have back when we were going through Mere Christianity in Season 1 of the podcast:

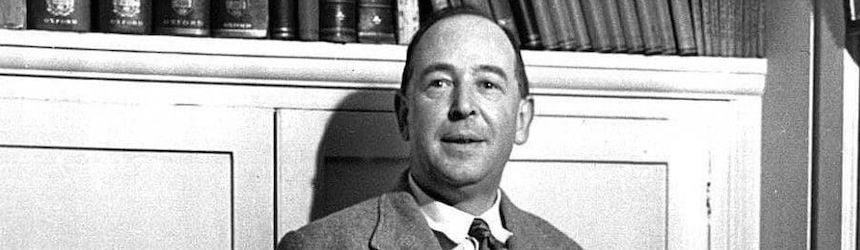

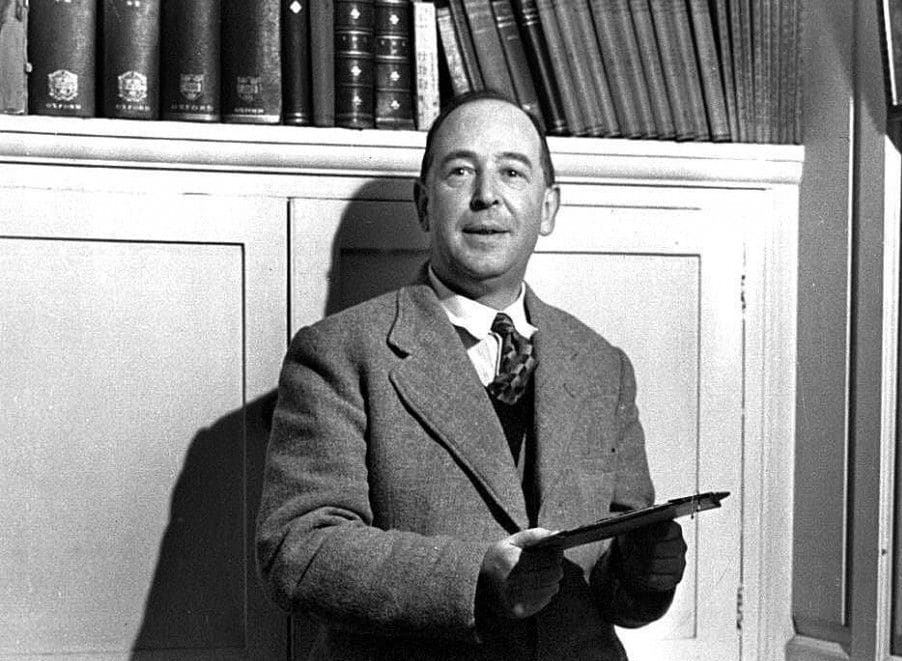

Given his prodigious output, it’s very hard to succinctly communicate the full genius of C.S. Lewis. Therefore, to give a broader sampling of his wisdom, in this series I’m going to be selecting four of my favourite books by Lewis and then examining some of the ideas to be found between their covers. The books we’ll be looking at will be Mere Christianity, The Great Divorce, The Screwtape Letters, and we’ll then close with The Four Loves.

After The Chronicles of Narnia, Lewis’ most well-known book is his seminal work on apologetics, Mere Christianity. The chapters of this book originally began life as radio broadcasts during World War Two. Over the course of the book, Lewis defends the Christian worldview. Matt and I go through this book chapter-by-chapter in Season 1 of our podcast, Pints With Jack, although back then the podcast was named after Lewis’ pub, The Eagle and Child.

1. A common Christianity

You don’t have to go far into this book to uncover treasure. For example, readers shouldn’t skip over the Preface of the book because in it Lewis explains what he is attempting to do, which is to defend what he calls “Mere Christianity”. Jack explains that he’s going to ignore denomination disputes and instead focus on explaining and defending the essentials of Christianity.

Although some people describe themselves as “a Mere Christian”, Lewis doesn’t set up Mere Christianity as its own denomination or as an alternative to the ancient creeds of the Church. He simply says that “Ever since I became a Christian I have thought that the best, perhaps the only, service I could do for my unbelieving neighbours was to explain and defend the belief that has been common to nearly all Christians at all times”. He felt compelled to do this because he thought that few others were defending this.

Lewis argues that this “Mere Christianity” is not a watered-down, vague, unsubstantial lowest-common denominator Christianity. Instead, he casts it as the highest-common factor Christianity, held across denominations and something which is both substantial and challenging. This is a sentiment which can be found in John-Paul II’s 1995 encyclical, Ut Unum Sint, where he quotes Pope John XXIII who said that “What unites us is much greater than what divides us.”

2. Choosing a denomination

Although Lewis purposefully avoids all denominational disputes in Mere Christianity, I think he gives really good advice about denominations.

He asks us to imagine a house. He describes the hallway as Mere Christianity and the rooms as denominations. He says that his goal in his book is to move people from outside the house into the hallway. However, he makes it clear that the hallway is not a place to remain indefinitely. He urges his readers to find their way into one of the rooms where “there are fires and chairs and meals”.

He cautions us though in the selection of a room. He says “…above all you must be asking which door is the true one; not which pleases you best by its paint and paneling. In plain language, the question should never be: ‘Do I like that kind of service?’ but ‘Are these doctrines true: Is holiness here? Does my conscience move me towards this? Is my reluctance to knock at this door due to my pride, or my mere taste, or my personal dislike of this particular door-keeper?’”

3. The Moral Law

After the Preface, Lewis spends the first portion of the book arguing for the existence of God and he does this by appealing to our common human experience.

Jack asks us to think about when we’ve heard people quarrelling. He points out that those who are quarrelling do not merely say that the other person’s behaviour displeases him. He says that “He is appealing to some kind of standard of behaviour which he expects the other man to know about… trying to show that the other man is in the wrong. And there would be no sense in trying to do that unless you and he had some sort of agreement as to what Right and Wrong are; just as there would be no sense in saying that a footballer had committed a foul unless there was some agreement about the rules of football”.

So from this, it appears that there is a Moral Law which exists. Over subsequent chapters Lewis looks at the possible origin for this Moral Law. Is it simply a matter of personal taste? Is it simply cultural convention? Is it simply instinct or taught to us in education? Lewis concludes that none of these are sufficient and starts building a cumulative case that this Moral Law is grounded in Moral Law Giver, God.

4. The Argument From Desire

This isn’t the only argument Jack gives for the existence of God. Although not presented as a formal syllogism in rigorous philosophical terms, he argues that our innate desires point to a world beyond this one.

He first observes that this world cannot fully satisfy us. Inevitably, it will let us down. “How will we respond when this happens?”, he asks. The hedonist will simply try and consume more – a new wife, a new job, a new car… The stoic will simply try and grin and bear it. Lewis says that the Christian, however, draws a different lesson:

The Christian says, “Creatures are not born with desires unless satisfaction for those desires exists. A baby feels hunger well, there is such a thing as food. A duckling wants to swim: well, there is such a thing as water. Men feel sexual desire: well, there is such a thing as sex. If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

Although perhaps not the most rigorous of proofs for God, Dr. Peter Kreeft, I personally find that this argument resonates most deeply with my own personal experience.

5. The Use of analogies

One cannot read Mere Christianity without noticing how often Lewis uses imaginative analogies to bolster his arguments and make different philosophical ideas easier to understand.

For example, in one chapter, Jack breaks down morality into three distinct parts. However, he does so by asking us to imagine a fleet of ships travelling across the ocean. For the fleet to make it safely home, three important factors must be present….

First of all, the ships must remain in formation and not crash into each other. Secondly, the ships themselves must be in good working order so that they can be steered correctly. Lastly, the ships must travel in the right direction in order to make it to their destination.

Lewis then draws parallels to morality. We must act rightly in relation to each other – we can’t be crashing into each other. We must be rightly-ordered internally – if we can’t control ourselves, it won’t be long before a collision is inevitable. Lastly, we must consider our teleology, our ultimate purpose, which is informed by the Creator who made us.

6. Faith and Works

Rather than stoking the fire of animosity between denominations, Lewis addresses the Reformation issue of the relationship between faith and works in an attempt to affirm what all Christians affirm.

Which is more important, faith or works? Lewis says that’s like asking which blade in a pair of scissors is more important. Discarding the caricatures of the Protestant and Catholic positions, he quotes St. Paul’s epistle to the Philippians which seems to synthesize both faith and works in a single sentence. He says:

The first half is, “Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling”-which looks as if everything depended on us and our good actions: but the second half goes on, “For it is God who worketh in you” – which looks as if God did everything and we nothing… You see, we are now trying to understand, and to separate into water-tight compartments, what exactly God does and what man does when God and man are working together. And, of course, we begin by thinking it is like two men working together, so that you could say, “He did this bit and I did that.” But this way of thinking breaks down. God is not like that. He is inside you as well as outside: even if we could understand who did what, I do not think human language could properly express it. In the attempt to express it different Churches say different things. But you will find that even those who insist most strongly on the importance of good actions tell you you need Faith; and even those who insist most strongly on Faith tell you to do good actions.

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

7. Forgiveness

Mere Christianity is not simply a book of dry doctrine. Personally, when I read it, I often find myself challenged concerning the state of my soul. No chapter perhaps best illustrates this better than the chapter on forgiveness.

Lewis says that he used to think that the most unpopular doctrines of Christianity related to sex, but perhaps it is, in fact, Christianity’s teaching of forgiveness. This might surprise us. After all, doesn’t everyone admit that forgiveness is a wonderful thing? Jack says we say this when we are the ones seeking forgiveness. However, when we are the ones who need to do the forgiving, we complain and howl in anger at the injustice of it all!

Quite rightly, Lewis reminds us that right at the heart of Christianity is the commandment to forgive our enemies, with Jesus’ harsh words concerning those who refuse to forgive. However, Lewis doesn’t leave it there…

Jack says that when he was a child he was told to “Hate the sin, but love the sinner”. He thought this was ridiculous. How was it possible to separate a man from what the bad things that he did? However, he eventually realized that there was one person for whom he had been doing this his entire life…himself.

He considers Christ’s command to love our neighbour as ourselves. I don’t know about you, but I’ve always focussed on the first part of that sentence, to love my neighbour. However, Lewis invites us to first consider the second part of that sentence…to love my neighbour as myself. How do I love myself? With a little bit of introspection, we realize that we don’t always like ourselves or the things that we do. This means that when I love my neighbour, I don’t have to pretend that he is nice when he is not, or that the things that he does are good when they are bad. Instead, I have to do for him what I do for myself, seek his good and hope that next time he will make a better choice and ultimately become a better man.

Christ does not forgive me because I didn’t really do anything wrong. He does so because He is good…and to be a Christian means to forgive the inexcusable because God has forgiven the inexcusable in me.

8. The Trilemma

One of the most well-known passages in Mere Christianity is C.S. Lewis’ “Trilemma”. Lewis did not invent this argument, but he did greatly popularize it.

Lewis is asking the most fundamental question one can really ask: who is Jesus? After all, Jesus made some pretty bold claims, not least of which was the ability to forgive sins. It’s one thing to say that you forgive someone who wrongs you, it’s quite another to tell someone that you forgive them for their sins against other people!

Lewis then addresses the person who says that Jesus was a great moral teacher, but he wasn’t God. Lewis rips this assertion to shreds, saying that this is the one thing which we cannot say! If we assume that the New Testament to be a record of what Jesus Himself said, we only have three options. He was either a liar, a lunatic or the Lord. Lewis explains:

A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic – on a level with the man who says he is a poached egg-or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God: or else a madman or something worse. You can shut Him up for a fool, you can spit at Him and kill Him as a demon; or you can fall at His feet and call Him Lord and God. But let us not come with any patronising nonsense about His being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

Lewis liked this argument so much that he reuses it in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe when Professor Kirk explains to the children why they should believe Lucy’s story about finding a magic world in the wardrobe.

9. The Purpose of Christianity

As my podcast co-host Matt and I worked through Mere Christianity chapter-by-chapter, one thing which jumped out at us was Lewis’ assessment of the purpose of Christianity. He says:

It is easy to think that the Church has a lot of different objects — education, building, missions, holding services. Just as it is easy to think the State has a lot of different objects — military, political, economic, and what not. But in a way things are much simpler than that. The State exists simply to promote and to protect the ordinary happiness of human beings in this life. A husband and wife chatting over a fire, a couple of friends having a game of darts in a pub, a man reading a book in his own room or digging in his own garden — that is what the State is for. And unless they are helping to increase and prolong and protect such moments, all the laws, parliaments, armies, courts, police, economics, etc., are simply a waste of time. In the same way the Church exists for nothing else but to draw men into Christ, to make them little Christs. If they are not doing that, all the cathedrals, clergy, missions, sermons, even the Bible itself, are simply a waste of time. God became Man for no other purpose

Mere Christianity

In the last chapter we were considering the Christian idea of “putting on Christ,” or first “dressing up” as a son of God in order that you may finally become a real son. What I want to make clear is that this is not one among many jobs a Christian has to do; and it is not a sort of special exercise for the top class. It is the whole of Christianity. Christianity offers nothing else at all.

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

Lewis sees that the central purpose of Christianity is to become another Christ. This comes about by sharing in God’s divine life. We receive our natural life from our parents, but we receive divine life from God, principally, he says, through faith, baptism and Holy Communion. This brings about a transformation which he compares to tin soldiers coming to life. Although he never uses the term, Lewis is describing theosis, which is a term often used in Eastern Christianity to describe the transformation which comes about when, in the words of St. Peter, we become “partakers of the divine nature”.

So there are some of my favourite themes of Mere Christianity. Next time we’ll be looking at The Great Divorce…

Today’s post is a continuation of yesterday’s article, introducing the readers to twenty things they might not know about C.S. Lewis…

11. Lewis addressed the nation during World War Two

After the success of his book, The Problem of Pain, Lewis was invited by the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) to speak on the radio to the nation during World War Two. These radio addresses later became the basis for one of Lewis’ best known books, Mere Christianity. As well as arguing for the existence of God, he used these broadcasts to defend the basic tenets of Christianity which are held across all Christian denominations.

12. He wrote many books, across many different genres

Mere Christianity was just one of the thirty or so books Jack wrote. What is particularly amazing about his vast literary output, even aside from the fact that he wrote every line with a dip pen, is that his works are of many literary styles. Lewis produced apologetics, fairy tales, science fiction, essays, autobiography, poetry and anthologies, as well as his academic work in literary criticism. In fact, you might say that he was a “Jack of all genres”…. 😉

All these successful books earned Lewis considerable wealth, but he gave away about two thirds of his income. He did this anonymously through The Agape Fund which he established.

13. There’s more to Narnia than you might think…

Probably Lewis’ most well-known works are The Chronicles of Narnia. Many of these have received TV and movie adaptations. These books were read to me as a child and, while the Narnia stories seemed to me somehow familiar, I didn’t fully grasp the Christian nature of these books until much later. However, Lewis was very quick to argue that Narnia wasn’t simply Christian allegory. Instead, he called it an “imaginative supposal”. He said:

Suppose there were a Narnian world and it, like ours, needed redemption. What kind of Incarnation and Passion might Christ be supposed to undergo there?

C.S. Lewis

Lewis understood the power of story-telling and its ability to smuggle ideas past our “watchful dragons” of prejudice. Stories allow us to encounter ideas afresh and with renewed potency. He had been affected by this himself, many years before when he read George MacDonald’s Phantastes, which he described as baptising his imagination.

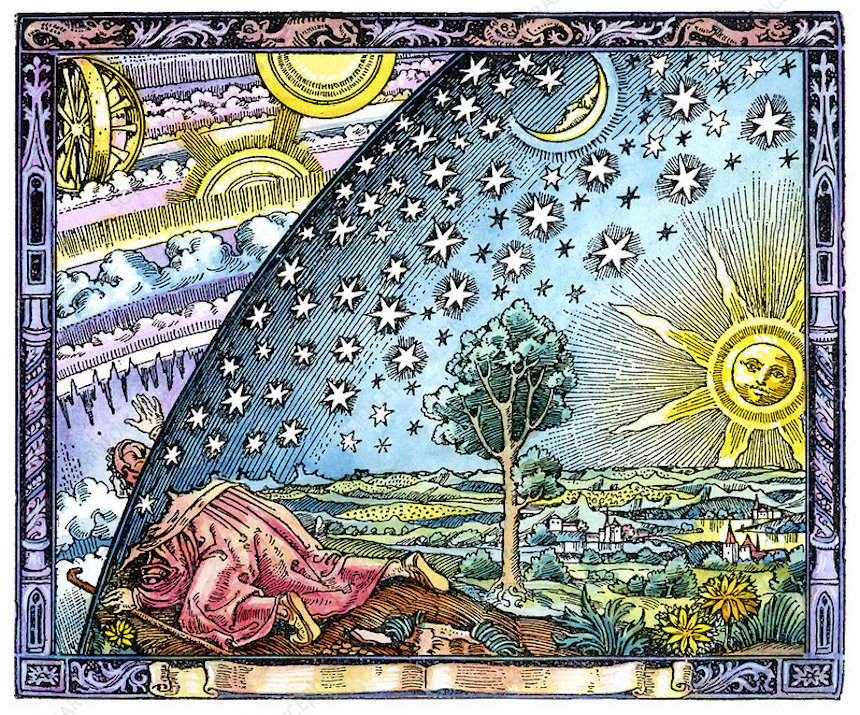

However, there are even more layers to the Chronicles of Narnia! About ten years ago, Dr. Michael Ward (a convert to Catholicism and the 100th priest of the newly-formed Anglican Ordinariate), published his book Planet Narnia, which argued convincingly that Lewis had based The Chronicles of Narnia upon the medieval cosmos. Each of the books correspond to one of the seven heavens and planets. For example, Prince Caspian is associated with the planet Mars which is, in turn associated with war and trees, motifs which we find interlaced throughout that book.

14. A pen friend to many

Not only was Lewis a “man of letters”, he was also a prolific letter-writer. For example, he regularly corresponded with his Irish childhood friend, Arthur Greeves, for over half a decade!

With Lewis’ celebrity, came many more letters, sent to him by adults as well as children. Jack took this responsibility very seriously and spent several hours a day writing responses to the avalanche of fan mail. There’s even an adorable letter from a mother whose child was worried that he loved Aslan more than Jesus.

15. He was snubbed at Oxford, but recognised at Cambridge

Despite his acclaim and popularity as a lecturer, Lewis was many times overlooked for promotion at Oxford University. The commonly accepted reason for this was that he wrote and spoke openly about his Christianity. Many felt it unbecoming of a man in his position, particularly one who didn’t even belong to the Theology Faculty. Fortunately, Cambridge University created a position specifically for him which, after some persistent pestering, he eventually accepted.

This wasn’t the only prize he was invited to accept. Lewis was offered a CBE (Commander of the British Empire) by the Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1951, but Lewis declined it, saying that he feared it might politicise his apostolate.

16. He wasn’t Catholic, but often sounded a lot like one

Many Catholics are surprised to discover that Lewis wasn’t actually a Catholic himself. This is understandable when one looks at some of Lewis’ beliefs. For example, he wrote about the Sacraments, spoke highly of the Blessed Sacrament, he believed in Purgatory and praying for the dead and regularly went to auricular confession to an Anglican priest.

Although he tried to avoid talking about his opposition to Catholicism, when pressed he cited the authority of the Pope and the veneration of Our Lady as his chief complaints. However, his Catholic friend Tolkien blamed what he called Lewis’ “Ulsterior Motive”, suggesting that the deep-seated distrust of Catholics which he had been taught as a boy in Ireland never entirely left him. Lewis himself admits to this kind of childhood indoctrination when he recounts his first meeting Tolkien:

At my first coming into the world I had been (implicitly) warned never to trust a Papist, and at my first coming into the English Faculty (explicitly) never to trust a philologist. Tolkien was both

C.S. Lewis, Surprised By Joy

Despite Jack’s resistance to embracing Catholicism, he is very much loved by Catholics. Both Pope St. John-Paul II and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI were very familiar with his work and spoke of it. Not only that, but many, many people credit Lewis, at least in part, with their conversion to Catholicism. This list of people includes those such as Dr. Peter Kreeft, Fr. Dwight Longernecker, Thomas Howard, as well as Lewis’ own secretary, Walter Hooper.

17. He lived most of his life as a bachelor, but married late in life

Lewis had lived most of his life as a bachelor. However, among the many letters he received from fans, one was from an American poet and writer named Joy Gresham. The two quickly developed a firm friendship. Joy visited England and eventually moved there with her two sons. When it seemed that the British Government was going to force them to leave the country, Lewis offered her a civil marriage so that she and her children could legally stay in England.

Unfortunately, shortly after they had obtained a civil marriage certificate, Joy was diagnosed with cancer. She was not expected to live long. Suddenly faced with the possibility of losing her, Jack realized his deeper feelings for his friend. They were married at her hospital bed by one of Jack’s friends who was an Anglican priest. Afterwards, the clergyman prayed and laid hands on Joy. To everyone’s surprise, she was granted a remission of four years before the cancer returned. Heartbroken by her death, he chronicled his mourning in his moving book, A Grief Observed.

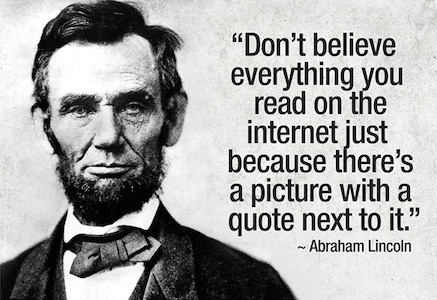

18. He is probably one of the most misquoted men on the Internet

As we all know, Abraham Lincoln warned us not to believe all quotations we see on the Internet! This is particularly true of Lewis, who seems to have his name attached to many quotations which he never actually said.

In fact, when I was in Oxford a few weeks ago, while looking at the various Inklings-themed walking tours, I found one which cost a whopping $335, but which, even aside from the numerous spelling mistakes on the website, included this quotation attributed to C.S. Lewis:

“You are never too old to set another goal or to dream a new dream”

Not C.S. Lewis!

Unfortunately, he never said it and I find that people on the Internet don’t appreciate it when I point such things! I would recommend that if anyone would like to verify a C.S. Lewis quotation, that they look it up in William O’Flaherty’s book, The Misquotable C.S. Lewis.

19. His death was overshadowed

Lewis died in his bed on November 22nd, 1963 at the age of 64. This was the same day on which Aldous Huxley died, and the same day on which President John F. Kennedy was killed. As such, Lewis’ death was largely overlooked as JFK’s assination dominated the news that day and in the subsequent weeks.

Jack’s funeral was small and his brother, Warnie, who had always struggled with alcoholism, was finding comfort at the bottom of a bottle of whisky.

20. He won most arguments, except one

Lewis’ secretary, Walter Hooper likes to say that he lost every argument he ever had with Jack…except one. Lewis was convinced that nobody would continue reading his books following his death, whereas Hooper said he was certain that their popularity would continue. Not only would Hooper be vindicated by history, he would have a hand in ensuring that his friend’s legacy would endure.

In the years following Lewis’ death, Hooper released a number of new works, previously unpublished, including several volumes of Jack’s letters. However, Hooper demanded that with each new book he gave to the publishers, that they re-release two of Jack’s older works, thus keeping his books continuously in print.

Today Lewis’ popularity is greater than ever. His books continue to sell in large numbers and Netflix recently purchased the rights to The Chronicles of Narnia! Six years ago on the 50th anniversary of Jack’s death, he was officially recognised at Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey (London) as one of the great British writers. The Episcopal Church have even honoured him with a Collect in their Liturgical Calendar:

“O God of searing truth and surpassing beauty, we give thee thanks for Clive Staples Lewis, whose sanctified imagination lighteth fires of faith in young and old alike; Surprise us also with thy joy and draw us into that new and abundant life which is ours in Christ Jesus, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen” – Collect of the Episcopal Church

Collect of the Episcopal Church

Part 1 | Part 2

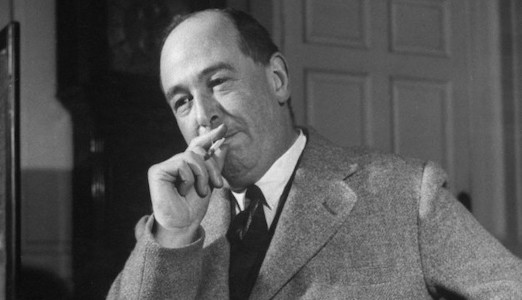

I was recently a guest on two episodes of The Counsel of Trent podcast to talk about C.S. Lewis. We spent the first episode simply talking about his life. Lewis was a man who left an indelible mark on the Twentieth Century. However, despite being such an influential figure, today many people only know him for his Chronicles of Narnia, and almost next to nothing about the man himself.

Therefore, in this article I would like to introduce you more fully to the man behind the Lion, and the author behind works which have deeply shaped modern Christianity and apologetics. If you would like to listen to the audio version of these articles, click here.

1. He wasn’t English

Often I have found people assume that C.S. Lewis was English, particularly if they have listened to one of the few remaining audio recordings of him. Lewis was, in fact, born in Belfast, Northern Ireland in 1898. He was, however, educated in England and lived in Oxford for most of his adult life.

2. He had several names…

He was baptised Clive Staples Lewis, but that wasn’t what his friends called him. When Lewis was about four, his dog, Jacksie, died. From then onwards, he stubbornly refused to respond to any other name, although it was eventually shortened to “Jack”. This is why the name of my podcast is Pints with Jack, the “Jack” in question being C.S. Lewis himself.

3. Jack experienced tragedy as a child

Lewis’ mother died of cancer when he was ten. He writes about it movingly in his spiritual autobiography, Surprised By Joy, describing it as follows:

“…all settled happiness, all that was tranquil and reliable, disappeared from my life”

C.S. Lewis, Surprised By Joy

The young Jack was soon afterwards sent to boarding school in England. He disliked England immediately and hated most of his schooling, so much so that in his autobiography, he names one of the schools he attended after one of the most notorious World War Two concentration camps, Belsen. Fittingly enough, the headmaster at that school would later be committed to an asylum.

4. Lewis wasn’t always a Christian

Most people who have heard of Lewis will know that he was a famous Christian of his generation. However, he was not a Christian all of his life. He was raised in the Church of Ireland, but became an Atheist as a teenager. There were several reasons for this…

Lewis loved the old Pagan myths, particularly those of the Norse. As he received his education in classics, he was told that Paganism was all false, whereas Christianity was entirely true. Not only did this assessment seem wrong to the young Lewis, but since he saw clear parallels between the two, he assumed that both Paganism and Christianity were simply fanciful stories.

Like many who embraced Atheism, the problem of pain and suffering also loomed large in Jack’s mind. He couldn’t reconcile a good God with the world he saw around him or with the pain he himself had endured in his life. He would often quote the Epicurean poet Lucretius who wrote:

Had God designed the world, it would not be

Lucretius (Epicurean Poet)

a world so frail and faulty as we see

5. He was a war veteran

Jack fought in World War One. In fact, he arrived at the front line on his nineteenth birthday. After being wounded in combat about a year later, he returned home.

During his training he had met a young man named Paddy Moore. The two had agreed that if one of them died, that the other would look after his family. Unfortunately, Paddy did not return from the trenches. Lewis was true to his word, living with and taking care of both Paddy’s mother, Janie, and Paddy’s sister, Maureen, for the rest of his life.

6. Jack was really, really clever…

Upon returning to Oxford after the war, Lewis excelled in his studies, earning multiple degrees. He got a First in Greek and Latin literature (“Moderations”), Philosophy and Ancient History (“Greats”), and finally in English.

It’s clear that Lewis was very intelligent, particularly when it came to language. He was, unfortunately, terrible at mathematics. In fact, his inability with numbers nearly barred his entrance to Oxford. Fortunately, upon returning from war, his military service granted him a dispensation from those exams.

7. He became a theist before becoming a Christian

Over time, Lewis started to become discontented with the imaginative and explanatory power of Atheism. He had originally embraced Atheism, in part, because of the cruel and unjust nature of the universe. However, as he would later argue in Mere Christianity:

…how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust?

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

Jack moved through a number of philosophical evolutions before he finally accepted the inevitable. In his autobiography he writes:

You must picture me alone in [my] room…, night after night, feeling… the steady, unrelenting approach, of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me. [I eventually]…gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England”.

C.S. Lewis, Surprised By Joy

He was not yet a Christian, but the seeds had already been sown…

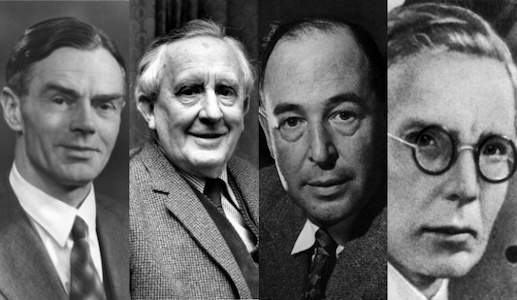

8. He really loved his friends

Contrary to some depictions of Lewis, he was not an isolated stoic academic. He loved good beer and good conversation. He really loved his friends and they would play a huge role in his life, particularly J.R.R. Tolkien, the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. In fact, Tolkien fans owe a great debt of gratitude to Lewis, as he was for a long time the only audience for these works and he did much to encourage Tolkien to finish them and get them published. Unfortunately, Tolkien disliked much of Lewis’ work, even The Screwtape Letters, a book which Lewis dedicated to him!

Many other names could be added to the list of Lewis’ close friends, such as Hugo Dyson, Charles Williams and Owen Barfield. All of these men shared a love of literature. In The Four Loves, Lewis would write:

Friendship is born at that moment when one person says to another: ‘What! You too? I thought I was the only one!’

C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves

Later these men would come together to form The Inklings, a literary discussion group where they would debate ideas and where they would read their work to each other. They would meet on Tuesday mornings in their favourite pub, The Eagle and Child, affectionately known to locals as The Bird and Baby, but they would also meet on Thursday nights in Lewis’ rooms at Magdalen College where they’d have a drink and smoke.

9. Speaking of smoking, Lewis really loved tobacco

I recently came across a biography of Lewis which estimated that he smoked sixty cigarettes a day! Now, since I’m marginally better at mathematics than Lewis, I sat down and worked out that, assuming he was awake for 14 hours a day and that it takes approximately five minutes to smoke a cigarette, that he spent a third of his waking life smoking!

Last year I visited Lewis’ home and although they had repainted the walls in the living room, they left the ceiling untouched so you could see how it was thoroughly stained by the nicotine!

10. His friends helped bring him to Christ

After converting to Theism, Lewis began to suspect that Christianity might be true. However, it was after a long, late-night conversation with Tolkien and Dyson that the last major obstacle was removed. Lewis had regarded Christianity as a myth like any of the other Pagan myths – “lies breathed through silver” – emotionally moving, but false.

Over the course of their conversation, Tolkien and Dyson helped Lewis see that Christianity was the true myth. For centuries before Christianity, man’s myths had intuited a dying and rising God. However, in Jesus of Nazareth, that myth became fact.

That’s the end of the first part of this series! The concluding part will be published tomorrow…

Part 1 | Part 2

Sorry for the delay! This is the episode where Matt and I sit back and reflect on this past season going through The Great Divorce chapter by chapter.

S2E23: The Great Divorce Retrospective (Download)

If you enjoy this episode, you can subscribe manually, or any place where good podcasts can be found (iTunes, Google Play, Podbean, Stitcher, TuneIn and Overcast).

Time Stamps

In case your podcast application has the ability to jump to certain time codes, here are the timestamps for the different parts of the episode.

01:53 – The Quote-of-the-week

03:17 – The Kilmer Letters

05:03 – My appearance of Reason and Theology

07:10 – Book discussion begins…

07:16 – What did you think of this Season?

11:53 – How has this Season changed you?

16:34 – What are the main themes you’ve seen?

30:28 – What kind of ghost would you be?

44:40 – The “Last Call” Bell

This week is a short episode and Matt and I are not discussing The Great Divorce. Instead I talk about an interaction I recently had on Facebook and how we’d all be better off if we took to heart a little piece of Lewisian wisdom…

Please send any objections, comments or questions, either via email through my website or tweet us @pintswithjack or message us via Instagram!

S2E2.5: “The language we use, and wishing black was a little blacker…” (Download)

If you enjoy this episode, you can subscribe manually, or any place where good podcasts can be found (iTunes, Google Play, Podbean, Stitcher and TuneIn).

Read more