Symbolism: The Cross

A little while ago I wrote a post about the earliest known depiction of the crucixion, the Alexamenos Graffito. During the ensuing Facebook discussion, the subject of the use of the cross in Christian art and worship was raised. This reminded me that I had myself that I would do a blog series on early Christian symbolism.

A little while ago I wrote a post about the earliest known depiction of the crucixion, the Alexamenos Graffito. During the ensuing Facebook discussion, the subject of the use of the cross in Christian art and worship was raised. This reminded me that I had myself that I would do a blog series on early Christian symbolism.

I’ve written before about abbreviations such as IHS and INRI, but I would like to expand upon this by examining early Christian symbols. So with that in mind, I’ve decided to do that today, beginning with probably the best known Christian symbol, the cross.

It may come as a surprise to many people to find out that, in the first few centuries, the use of the cross in Christian art and worship is somewhat unclear. Some historians and archeologists see this symbol throughout the historical record, while others claim that the cross is almost completely absent.

At first glance this might seem strange. Why is there such disagreement? Over the remainder of this post we will see why…

Why the dispute?

The main problem is that we have very few indisputable Christian images of the cross in the historical record prior to the Third Century. This is for two primary reasons:

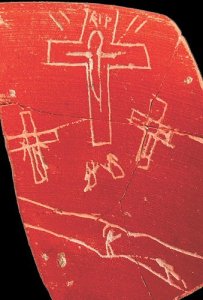

1. Cross, decoration or damage?

It’s often hard to tell whether a particular graphic is meant to be a cross, or whether it is just an ornamental flourish which just happens to be in a cruciform shape (T or X). In the early Christian images of bread, the loaves appear to be marked with crosses…but these could just be accidental wall scratches; it’s hard to say.

2. Low quality Graffiti

Many of the possible archaeological candidate images are graffiti. Since they have been hastily scratched and they are more open to alternative interpretation.

An Example

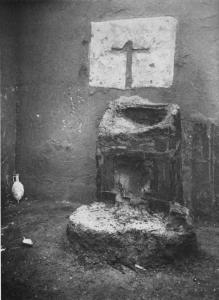

The picture below is of a room which was sealed during the Mount Vesuvius eruption in the First Century:

The Casa del Bicentenario, Herculaneum, Italy ~ AD 79

Many suggest that the piece of furniture is some kind of kneeler or altar and that, together with the imprint of the cross on the wall, it suggests that this was a Christian household. However, others have offered alternative explanations, such as suggesting that the imprint of the cross is simply from a wall bracket.

Why might Christians have not used this symbol?

Those historians who deny cross depictions in the early centuries have given a few explanations for this surprising omission:

1. Christians were secretive

If you read either the Church Fathers or the secular accounts of Christians, you often find the “discipline of the secret”, whereby Christians would guard jealously certain aspects of the Faith and refuse to reveal them to non-Christians. A common example of this was the Eucharist celebration. It is possible that, given the outrageous nature of the Christian claims concerning Jesus’ crucifixion, that Christians avoided using this symbol.

2. Crucifixions were commonplace

Up until the legalization of Christianity, crucifixion was still a common means of execution It has been suggested by some scholars that, since they were regularly reminded of the Saviour’s ordeal in the regular executions of criminals, Christians avoided using the symbol in artwork.

In future posts we will come back to the representation of crosses in Christian art, when we look at staurograms and other crypto-crosses.

The cross and early Christianity

Regardless of its use in early Christian art, the cross was certainly central to Early Christian belief. At the beginning of the Second Century, St. Ignatius of Antioch wrote the following:

I offer my life’s breath for the sake of the Cross, which is a stumbling block to the unbelievers, but to us is salvation and eternal life.

– Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Ephesians (Chapter 18)

We also find that the sign of the cross was a common practice in the Second Century:

…we have an ancient practice…from tradition… At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign.

– Tertullian, De Corona (Chapter 3)

I began this post by explaining that historians disagree as to the presence of crosses in early Christian art and worship. The critics claim that some people are just seeing crosses everywhere. Maybe that’s because the cross is a fundamental shape which we find throughout our world. Here are the words of St. Justin Martyr, also from the Second Century, speaking about the ubiquity of the cross:

Think for a moment and ask yourself if the business of the world could be carried on without the figure of the cross. The sea cannot be crossed unless the sign of victory – the [cross-shaped] mast – be unharmed. Without it there is no plowing; neither diggers nor mechanics can do their work without tools of this shape; … The power of this form is shown by your own symbols, on your banners and trophies, which are the insignia of your power and government – St. Justin Martyr, First Apology (Chapter 55)