Yesterday I shared a quotation on the subject of suffering from a book I recently finished, Jesus Among Other gods by Ravi Zacharias.

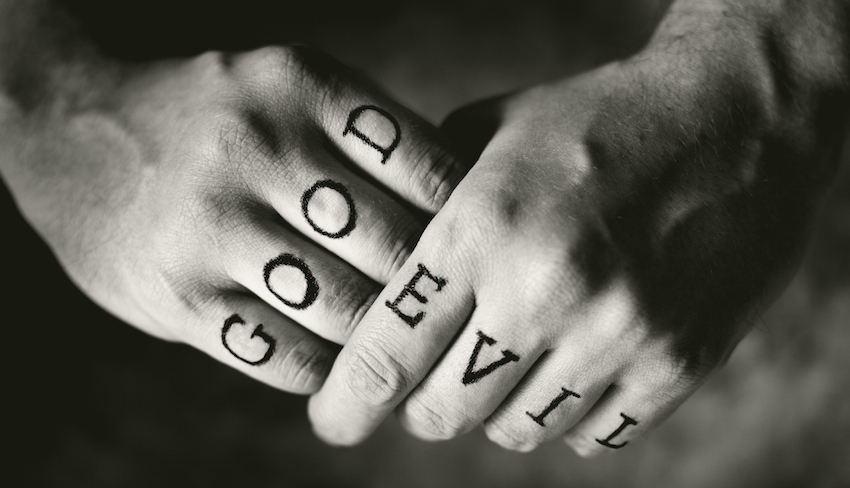

In that post, we saw that even to talk about good and evil we need an objective moral law, something which is rather difficult to explain while denying the existence of an eternal, transcendent God.

Today I’d like to offer a few more quotations from Zacharias’ book. For those of us who are involved in apologetics (which is, of course, every Christian!), he reminds us of a truth which we must keep forever at the front of our mind when speaking about the very difficult subject of pain and suffering.

How does a good God allow so much suffering? Immediately we enter into a very serious dilemma. How do you respond to the intellectual side of the question without losing the existential side of it? How do you answer…[those who are suffering] without drowning it all in philosophy?

– Ravi Zacharias, Jesus Among Other gods

Suffering is not simply a theoretical idea or only a subject for clever philosophical arguments, it is a very real reality with which people must live and it is a topic which is deeply emotionally charged.

Those who feel the pain… often shudder at how theoretical philosophical answers are. We do not like to work through the intellectual side of the question because we do not see where logic and philosophy fit into the problem of pain. If you have just buried a son or a daughter, or have witnessed brutality firsthand, this portion of the argument may bring more anger than comfort. Who wants logic when the heart is broken? Who wants a physiological treatise on the calcium component of the bone when the shoulder has come out of its socket? At such a time we are looking for comfort. We want a painkiller.

– Ravi Zacharias, Jesus Among Other gods

The solution to this problem is to balance delicately the intellectual and the emotional, speaking to both and neglecting neither:

We must not allow the anguish of the heart to bypass the reason of the mind. The explanation [of pain] must meet both the intellectual and the emotion demands of the question. Answering the questions of the mind while ignoring shredded emotions seems heartless. Binding the emotional wounds while ignoring the struggle of the intellect seems mindless.

– Ravi Zacharias, Jesus Among Other gods

When my Dad died earlier this year, I didn’t want a dry philosophy lesson. I wanted people to grieve with me, but who were ready to talk when the time came to grapple intellectually and spiritually with what had happened.